Hi, I’m Anthony! 👋 Every Week, I look at the 10% of startups that did not end up in the startup graveyard.

If you haven’t subscribed yet, join the other folks interested in startups by subscribing here:

Hello everyone!

VISA is one of those companies where people think they know what they do but cannot really explain what exactly they do. Myself included.

This piece will be part of a 3 part series of my summary of the fantastic episode by the Acquired podcast on Visa. As someone in the payments industry, writing this summary has been great fun for me, and I'm excited to share these insights with you.

This is part I of the Visa story:

Part I: The Seedling of Visa

Part II: The Birth of Visa

Part III: The Future of Visa and Payments

Let’s dive right in!

Visa Background

Visa is an important connector in the world of global financial transactions, extending far beyond its common perception as merely a credit card issuer. Visa is like an expansive, secure highway, facilitating swift and safe monetary transfers worldwide, whether it’s for a simple coffee purchase or a lavish international vacation.

At the heart of its operations, it provides a robust network that financial institutions utilize to offer Visa-branded cards. Each transaction made with a Visa card involves a modest fee paid by the bank to Visa, going back to the previous highway example, it collects a toll on every vehicle going through their robust highway.

This toll road business model is an incredible one for Visa, it has the 11th largest market cap in the world and operates at a net profit margin of ~53%, far ahead of any company of similar size.

The US Payment Industry History

To fully grasp Visa's ascent, we need to rewind to an era where cash and cheques were the norm. Each cheque presented its own set of challenges – costs for processing and a time lag that was far from ideal.

Eventually, merchants figured that instead of moving money daily, how about I just leave a tab for my customers and settle at the end of the month? And so They introduced charge accounts, enabling customers to accumulate charges and pay them off monthly. This not only streamlined transaction clearing to once a month but also significantly cut down operational costs.

Initially, these accounts were exclusive to individual stores. But soon, corporations like Standard Oil started to integrate the accounts across all their branches sending 250,000 unsolicited cards to all their customers for their charge accounts.

However, this system still isn't ideal for consumers and merchants alike. Imagine consumers lugging around dozens of cards, one for each store – hardly practical. Merchants, on the other hand, were navigating in the dark regarding the credit history of their customers with other establishments.

This unstable state pushes for a network to be formed, one where retailers get together and have a standardized charge account system.

Yet, this network was not without its ironies. By participating in this unified network, merchants inadvertently supported their competitors. Imagine a local bookstore and a national chain sharing the same payment platform. Each swipe of a customer's card at the local store indirectly reinforced the network that included the rival chain, effectively equipping their competition with the same transactional advantages. This paradox highlighted a fundamental tension in the new system, that collaboration for convenience at the cost of potentially aiding one's market rivals.

It is here where players such as Diners Club and American Express first arrived on the charge card scene.

Early players: Diners Club/American Express

Both Diners Club and American Express started out by targeting a specific group.

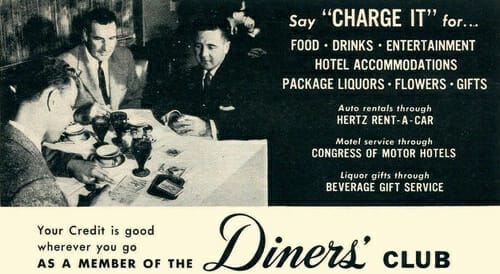

Diners Club, for instance, zeroed in on the restaurant industry, establishing a shared charge account system among restaurants. This strategy is shrewd, in the competitive but non-exclusive restaurant landscape, no single establishment expected lifetime loyalty from a diner. This approach facilitated an easier buy-in from restaurants, allowing them to collectively reap the benefits of the network without fearing the loss of their unique customer base.

Diners Club's model proved successful enough to levy charges as high as 7% on merchants, and they even implemented card fees for users. Yet, despite these fees, sustaining profitability was challenging. The cost of maintaining such a network, especially with the limited technology and the heavy reliance on manual processes, was substantial, and this is just within the confines of New York City.

American Express, observing Diners Club's success, decided to enter the fray. They launched a charge card program tailored for the business traveler, expanding the concept beyond the realm of dining and into broader commercial travel and also marking the entry of a bank-like entity into the scene.

The BankAmericard

Make me some loans

As charge cards gained traction, Bank of America spotted the perfect moment to revolutionize the market with their twist: introducing credit. This strategic move aimed to elevate their services in several ways:

Streamline their lending programmes

Make more money by giving out loans

Unlike charge cards, which required full monthly payment, this credit card allowed customers the flexibility to convert their spending into loans, offering a more streamlined, on-ramped approach to introducing consumer loans.

The credit card program didn't just increase the number of loans issued, it fundamentally changed the dynamics of money flow within the bank. Having credit programmes minimizes the amount of money actually leaving Bank of America.

Traditionally, loans involved a tangible cash exchange, the bank handed out cash, which the consumer spent, and the merchant eventually redeposited. This process, while straightforward, meant the actual cash left the bank's hands.

With the BankAmericard, this cycle was streamlined. The consumer goes directly to the store, pays with the credit card, transactions get authorised, and if merchants banks with Bank of America, no money leaves Bank of America, it is just a simple ledger update. This frees up capital and float for the bank.

And so they mailed almost 65,000 cards indiscriminately with the same credit limit to every customer.

Give me back my money

And of course, fraud happens.

The credit card loans are practically unsecured lending, and when you issue thousands of unsecured credit lines, as they did indiscriminately, you're practically inviting fraud.

There was $20 million of fraud within the first pilot program and 22% of the credit that they issued ended up being default or delinquent, which is five or six times of what their delinquency rate was before on traditional lending. These were daunting figures, enough to make any financial institution reconsider its strategy.

But Bank of America was undeterred. They saw the untapped potential in the credit card market and were prepared to weather the storm.

Their conviction paid off. Within three years, they not only brought fraud under control but also turned the program profitable. This success, however, was closely guarded – a secret strategy that kept competition at bay. As a result, within the first six years of the BankAmericard, only a handful of new credit cards emerged.

By being first to the new market of credit card, Bank of America can operate within a zone of uncertainty for many years. Competitors are looking to them to see whether this credit card thing works before launching their own. By keeping the profitability a secret, Bank of America is able to extend this zone of uncertainty build their moat, and sign up more merchants and consumers, securing their position as pioneers in a then-uncertain market (AKA productive uncertainty).

BankAmericard Network

Eventually, Bank of America let the cat of out the bag with the launch of the BankAmericard service organisation to license out their credit card program and network to banks across the country.

Licensee/franchisee would pay Bank of America a franchise fee and also a percentage of their transaction value. Within two years, a couple of hundred banks had signed up with six million cardholders across the country and beyond the country.

However, there was a problem.

Before franchising its network, BankAmericard usually operated within a closed-loop network. All parties of the transaction were their customer. There are no differences in the:

Banks of their consumer's card (Issuing Bank)

Bank of the merchant (Merchant/Acquiring Bank)

With the franchising, however, this was rarely the case.

The issuing bank and merchant banks are not the same party. This then transforms into an open-loop network. With the open loop network, there is a need for an interchange between different parties to enable systems to talk to each other and settle these transactions.

But here's the catch. Bank of America's network was designed for a closed loop, and they weren't equipped to address these complexities for their licensees. In their view, franchising was more about marketing than infrastructure development.

So the franchisee has to go back in time to how cheques used to work.

Merchants accept BankAmericards and collect invoices. At the end of a month, the acquiring banks would then take the invoices and individually mail the issuer banks to get the money. But this is all great for Bank of America, it’s just internal number movement and they have no incentive to change this.

Yet, it was precisely this inefficiency that planted the seeds for the emergence of Visa.

And that’s it for this week! In the next part, we will dive into The Birth of Visa. Stay tuned!

If you enjoy my post, please consider sharing it or subscribing, see you in the next piece!

— Anthony 🚀